La imagen y su doble | The image and its double

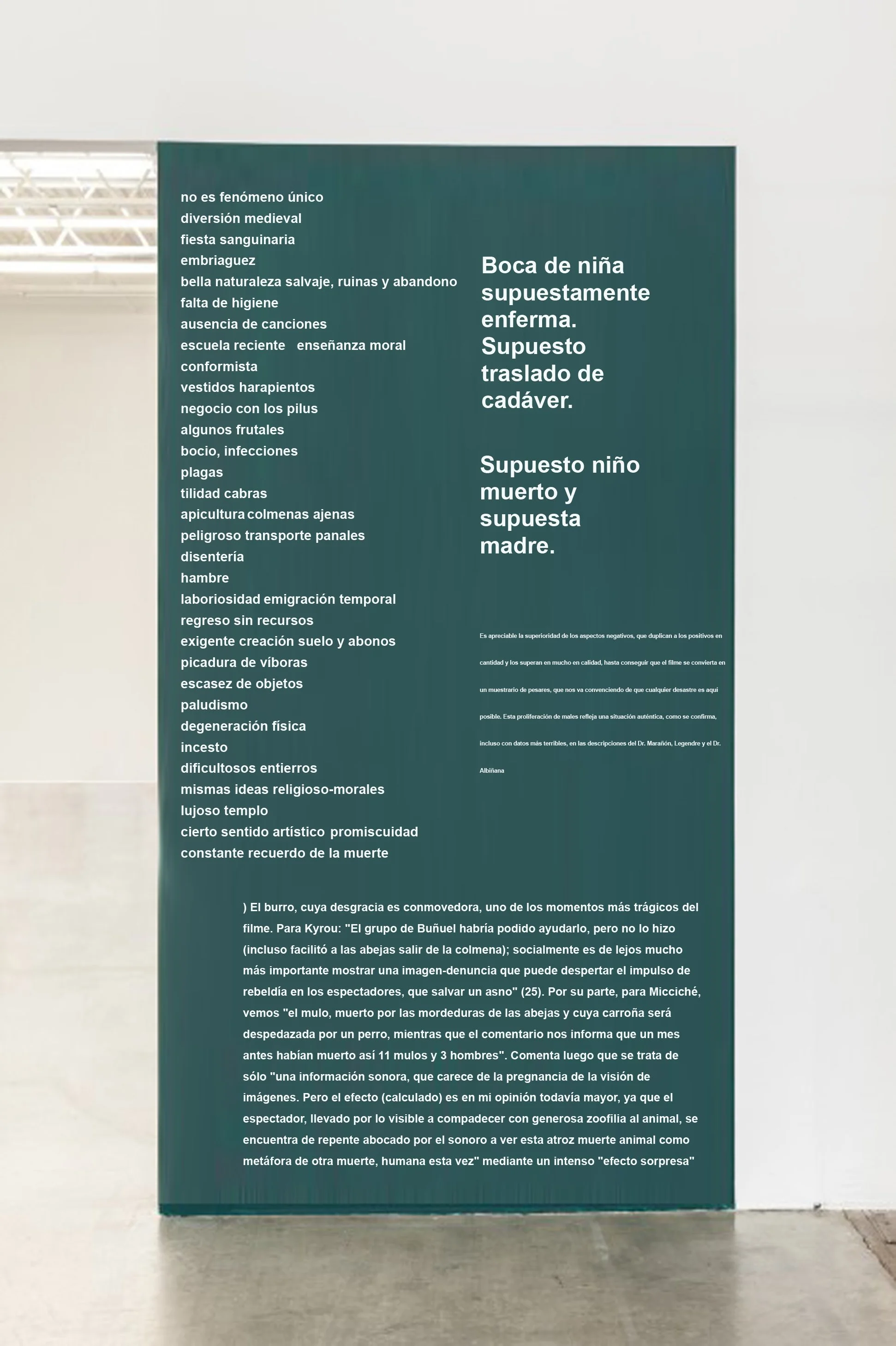

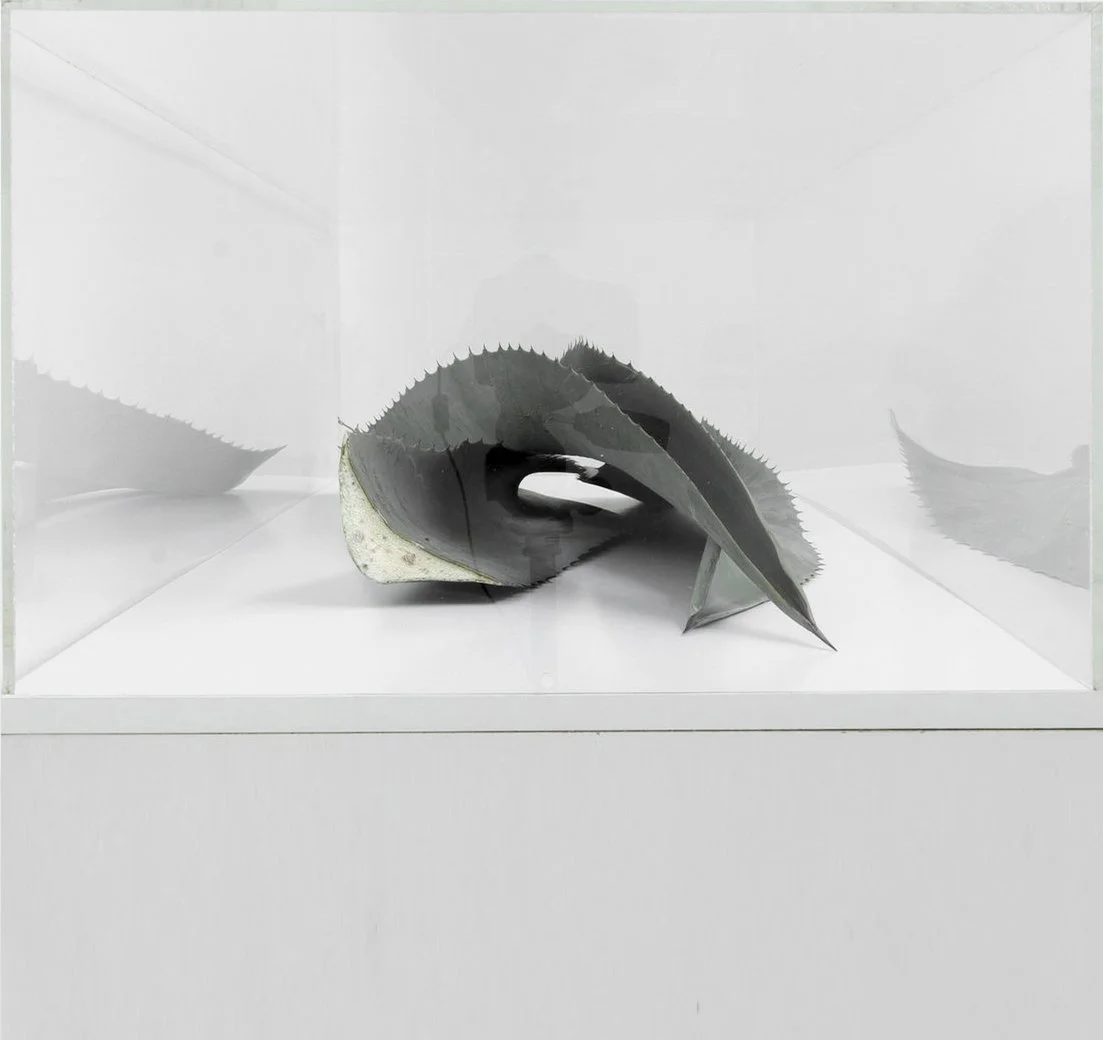

Nicolás Franco does not usually capture the photographic images we see in his works. His procedure is rather to process and reuse visual objects and printed material, driven by some archivist’s obsession whose purpose is not obvious. A number of his projects between 2005 and 2015 involved reproducing photographs and transferring images from one medium to another. These images could be considered in some sense documentary, either because they actually came from archival sources or because they were tracked down in books, films or periodicals where they once served some practical or artistic purpose, rarefied now by the procedures used to restore them. This visual material usually makes some oblique allusion to recognizable cultural, economic, geopolitical and technical processes that marked the course of the twentieth century.

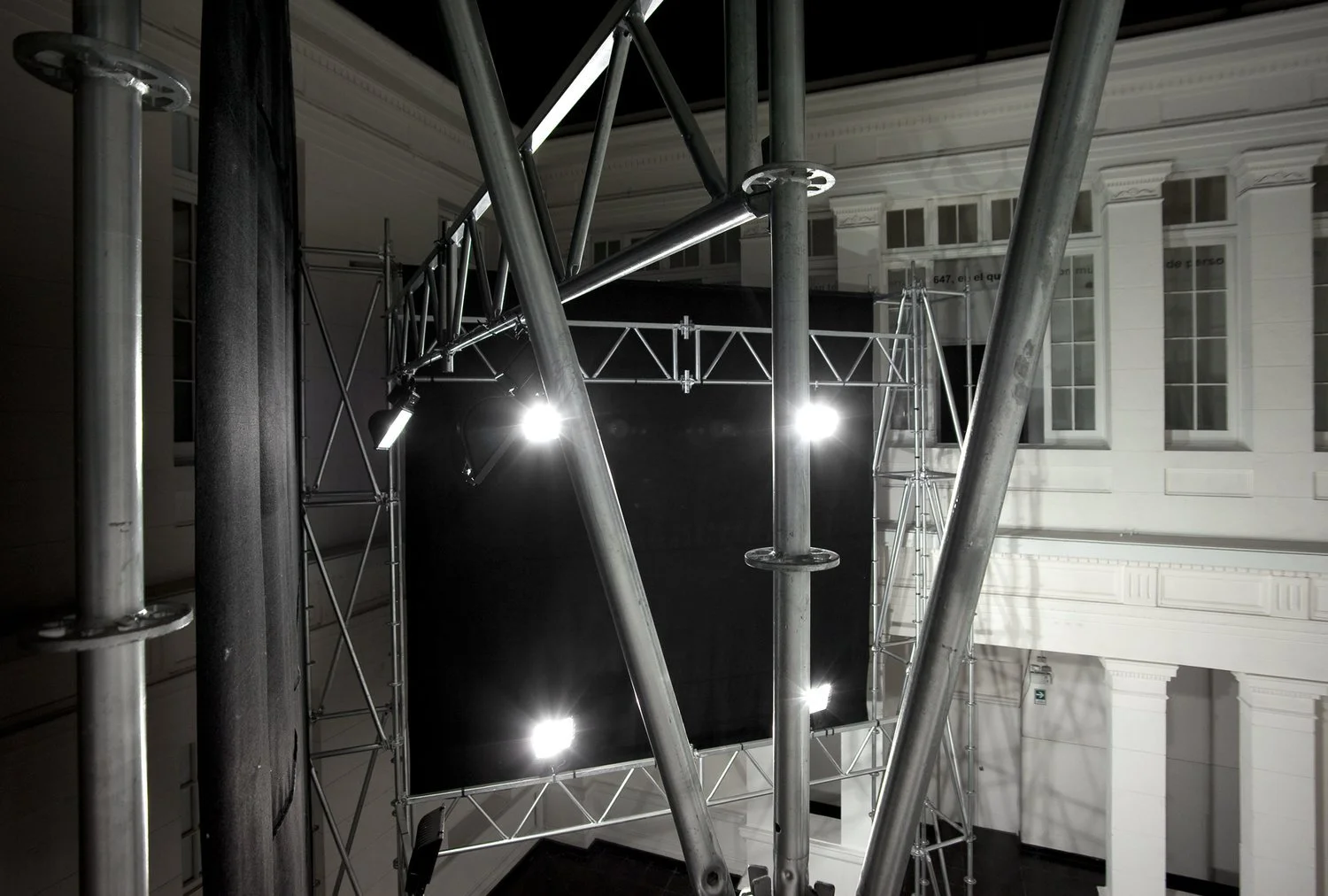

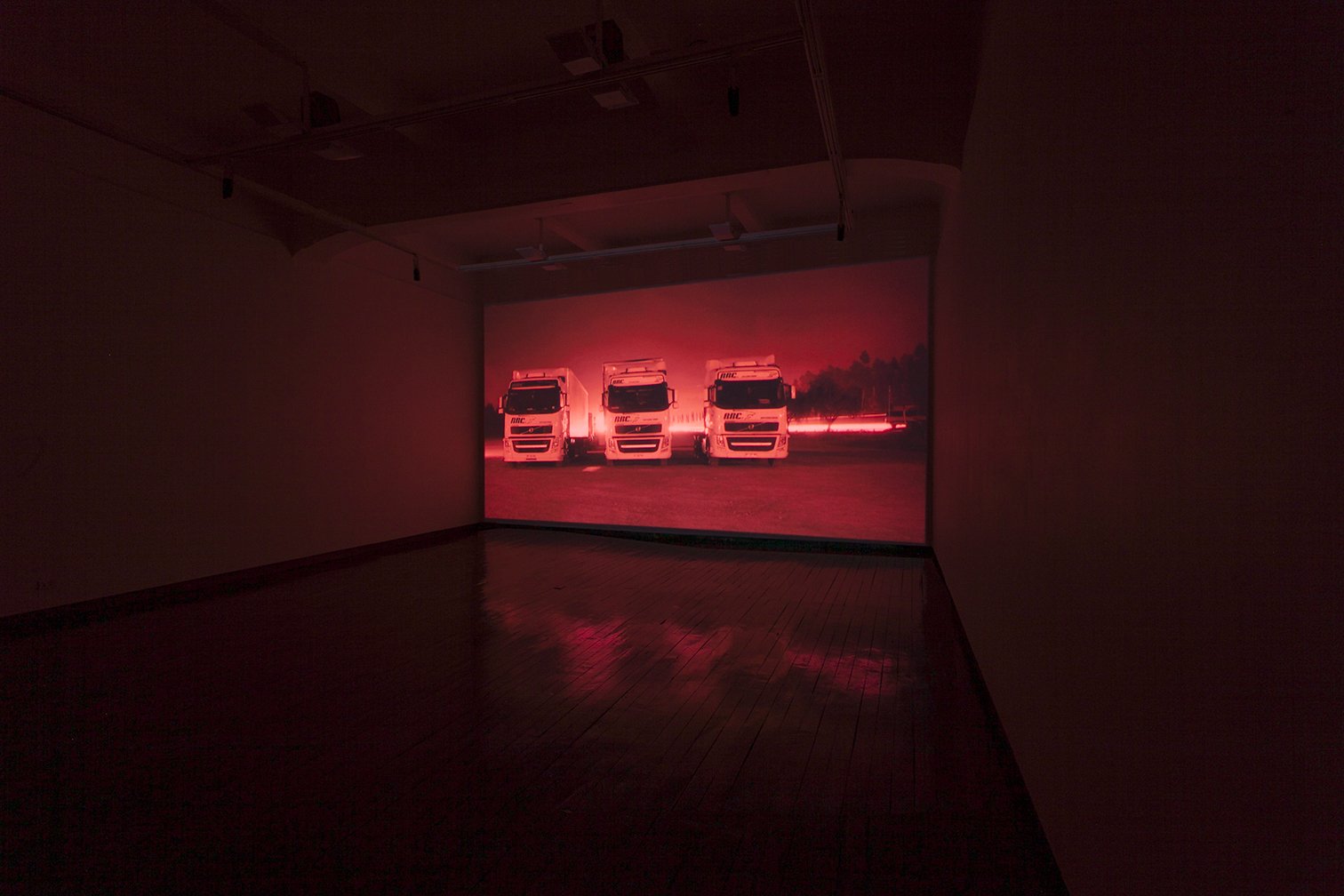

Film Still. HD video, BW, stereo, 27 minutes. Presented in Santiago in 2015 at Galería Macchina and the Video and Media Arts Biennial, National Museum of Fine Arts.